[Press Release]

The study shows that simple differences in membrane chemistry helped primitive cells grow, fuse, and keep genetic material together suggesting that physical properties guided life before genes did.

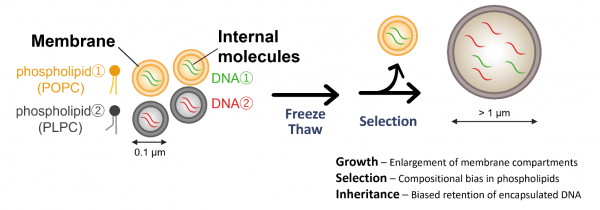

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the experimental workflow and key findings

Membrane compartments (vesicles) were prepared from two phospholipids with distinct acyl-chain structures, each encapsulating a different DNA species. Upon repeated freeze–thaw (F/T) cycles, the vesicles enlarged in size, and clear compositional biases toward PLPC—the lipid species with higher growth propensity—as well as toward the DNA molecules originally encapsulated within PLPC vesicles were detected. These results demonstrate that prebiotic environmental fluctuations by F/T cycling can drive processes of growth, selection, and inheritance in primitive membrane compartments. Credit: Tatsuya Shinoda & Natsumi Noda, ELSI

Modern cells are complex chemical entities with cytoskeletons, finely regulated internal and external molecules, and genetic material that determines nearly every aspect of their functioning. This complexity allows cells to survive in a wide variety of environments and compete based on their fitness. However, the earliest primordial cells were little more than small compartments where a membrane of lipids enclosed simple organic molecules. Bridging the divide between simple protocells and complex modern cells is a major focus of research into the origin of life on Earth.

A new study by a group of researchers, including scientists at the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at Institute of Science Tokyo, explores how simple cell-like compartments behave under physically realistic, non-equilibrium conditions relevant to early Earth. Rather than advancing a specific origin-of-life hypothesis, the work experimentally examines how differences in membrane composition influence protocell growth, fusion, and the retention of biomolecules during freeze–thaw cycles.

The research team studied the effect of lipid composition on protocell growth. The team created small spherical compartments called large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) using three kinds of phospholipids: POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine; 16:0–18:1 PC), PLPC (1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; 16:0–18:2 PC), and DOPC (1,2-di-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; 18:1 (D9-cis) PC).

“We used phosphatidylcholine (PC) as membrane components, owing to their chemical structural continuity with modern cells, potential availability under prebiotic conditions, and retaining ability of essential contents,” said Tatsuya Shinoda, a doctoral student at ELSI and lead author. However, there are small but crucial differences between these molecules. POPC has one unsaturated acyl chain with a single double bond. PLPC also contains one unsaturated acyl chain, but with two double bonds. DOPC has two unsaturated acyl chains with one double bond on each chain. As a result, POPC forms relatively rigid membranes, whereas PLPC and DOPC produce more fluid membranes.

LUVs were then put through freeze/thaw cycles (F/T) to simulate temperature cycles that cause physical changes in protocells. After three F/T cycles, POPC-rich LUVs formed aggregates of many vesicles in close contact, whereas PLPC- or DOPC-rich LUVs merged to form much larger compartments. Vesicles were more likely to merge and grow as their PLPC content increased. These findings clearly show that phospholipids with more unsaturated bonds were more likely to merge and grow. “Under the stresses of ice crystal formation, membranes can become destabilised or fragmented, requiring structural reorganisation upon thawing. The loosely packed lateral organisation due to the higher degree of unsaturation may expose more hydrophobic regions during membrane reconstruction, facilitating interactions with adjacent vesicles and making fusion energetically favorable.” remarked Natsumi Noda, researcher at ELSI.

But what does this mean for the origin of life? When LUVs merge, their contents could mix and interact. In the “soup” of organic molecules on a primordial Earth, these fusion episodes might have brought important molecules together where they could react and become more like what we recognise as cells today. The team verified this by studying how well 100% POPC and 100% PLPC LUVs retained DNA. Not only were PLPC vesicles better at capturing DNA before F/T, but with each F/T cycle, they retained more DNA than POPC vesicles.

Dry-wet cycles on the Earth’s surface and hydrothermal vents at the deep sea are the two most popular places where chemical and prebiotic evolution are believed to have taken place. The current study suggests that an icy environment might also have played an important role. On a primordial Earth, F/T cycles would take place over long periods. The formation of ice would exclude solutes from the growing ice crystals and increase the local concentration of organic molecules and vesicles. Phospholipids with a higher degree of unsaturation form more loosely packed membranes, which facilitates vesicle fusion and content mixing. On the other hand, a compartment composed of more fluid phospholipids can become destabilised under freeze–thaw–induced stress, leading to leakage of its encapsulated contents.

Permeability and stability are contradictory requirements, and the composition of the lipid compartment that is “most fit” would change based on environmental conditions. “A recursive selection of F/T-induced grown vesicles across successive generations may be realised by integrating fission mechanisms such as osmotic pressure or mechanical shear. With increasing molecular complexity, the intravesicular system, i.e., gene-encoded function, ultimately may take over the protocellular fitness, consequently leading to the emergence of a primordial cell capable of Darwinian evolution,” concludes Tomoaki Matsuura, Professor at ELSI and principal investigator behind this study.

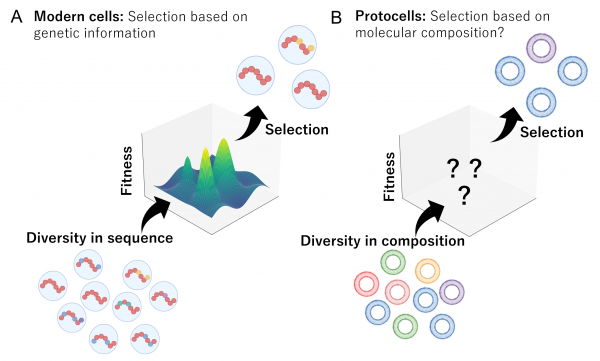

Figure 2. Evolutionary modes of modern cells versus protocells

(A) In modern lifeforms, cellular traits and functions are controlled by genetic information encoded in DNA sequences. Mutations generate sequence diversity, and when this diversity leads to differences in fitness, natural selection enriches variants with higher fitness in the next generation. (B) At the earliest stage of life, the “evolution” of primordial cells was likely far simpler. Diversity in molecular composition would have directly shaped protocell behavior through their physicochemical properties, allowing molecules with advantageous traits to be preferentially retained. Such composition-driven selection may have formed a primitive basis for evolutionary change. Credit: Tatsuya Shinoda & Natsumi Noda, ELSI

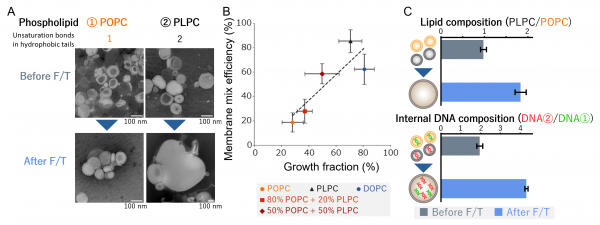

(A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of vesicles before and after F/T. Vesicles initially prepared at ~100 nm in diameter grew to several micrometers after F/T, with PLPC vesicles exhibiting markedly stronger growth than those made from POPC. (B) Relationship between the fraction of enlarged vesicles and membrane-mixing efficiency within the enlarged population. Each point represents a different lipid composition. The positive correlation indicates that lipid compositions with higher growth propensity also show more extensive membrane mixing upon growth. (C) Compositional selection from mixed vesicles. After F/T, the enlarged vesicle population was enriched in PLPC and in the DNA originally encapsulated within PLPC vesicles. These results demonstrate that growth-favorable lipid species selectively constitute the enlarged vesicles and that their encapsulated molecules are concurrently and preferentially inherited. Credit: Adapted from Chem. Sci.

Reference

Tatsuya Shinoda1, Natsumi Noda2, Takayoshi Watanabe2,3, Kazumu Kaneko4, Yasuhito Sekine2, and Tomoaki Matsuura*2, Compositional selection of phospholipid compartments in icy environments drives the enrichment of encapsulated genetic information, Chemical Science, DOI: 10.1039/d5sc04710b

- Department of Life Science and Technology, Institute of Science Tokyo, Japan

- Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI), Institute of Science Tokyo, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan

- MAQsys Inc., Kanagawa 213-0012, Japan

- Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Institute of Science Tokyo, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan

*Corresponding authors’ email: matsuura_tomoaki@elsi.jp (Tomoaki Matsuura)

Contacts:

Thilina Heenatigala

Director of Communications

Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI),

Institute of Science Tokyo

E-mail: thilinah@elsi.jp

Tel: +81-3-5734-3163 / Fax: +81-3-5734-3416

Tomoaki Matsuura

Professor

Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI),

Institute of Science Tokyo

E-mail: matsuura_tomoaki@elsi.jp