[Press Release]

New research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that Earth’s ancient atmosphere may have acted as a global chemical factory, naturally producing sulfur-containing molecules that would later become essential building blocks of life. The study suggests that before life existed, Earth’s sky was already generating complex organic compounds, challenging the long-held idea that such molecules emerged only after biology began on our planet.

Yellow elemental sulfur is shown on a laboratory spatula. Reed et al. discovered new chemical pathways which transform sulfur into key biological molecules. Credit: Shawn McGlynn

A multi-institution and international team of scientists from Colorado University’s Department of Chemistry and Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at the Institute of Science Tokyo, NASA, and other institutions revealed that key biological molecules can be produced from thin air. By conducting laboratory simulations of the early atmosphere, the researchers recreated conditions from more than three billion years ago. Their experiments mixed gases thought to be abundant on the early Earth—including methane, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide and nitrogen—and exposed the mixture to ultraviolet light, mimicking sunlight interacting with the planet’s primordial air.

Using sophisticated mass spectrometry, the research team detected a suite of sulfur-bearing organic molecules in the simulated atmosphere, including amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, as well as coenzyme M, a compound involved in metabolism. These findings indicate that Earth’s early sky was capable of producing a variety of biomolecule precursors in significant quantities.

When scaled to a planetary level, the results suggest that the early atmosphere could have produced enough cysteine to supply on the order of an octillion cells (a number followed by 27 zeros), a substantial amount even in a pre-biotic world. For comparison, the total biomass on Earth today is estimated at about one nonillion cells (a number followed by 30 zeros).

These sulfur molecules are critical to life as we know it; sulfur is a key component of many proteins and metabolic cofactors, and its chemical versatility supports a wide range of biological functions. Previously, many scientists believed that complex organic sulfur compounds could form only through biological activity or under highly localized conditions, such as near hydrothermal vents or alkaline springs with unusual chemistry. The new study implies that widespread atmospheric chemistry, driven by sunlight and simple gases, may have delivered many of the necessary molecular ingredients for life across the early planet.

According to Shawn McGlynn, co-author and Principal Investigator at ELSI, this work reframes how researchers think about the origin of life’s chemistry. He said that the findings show Earth’s early atmosphere was not just a passive backdrop but an active chemical engine capable of generating key molecules for life, and that early biology may have inherited chemical molecules as tools already present in the environment rather than inventing them from scratch. This perspective brings new insight into how life could have begun under widespread conditions, without requiring rare or specialized environments and emphasising life as a planetary process.

Traditional theories have focused on extraterrestrial delivery of organic molecules, such as amino acids carried by meteorites, as a major source of early pre-biotic compounds. While those sources may have contributed some ingredients, the new work demonstrates that atmospheric processes alone could have produced a global supply of certain biomolecules, potentially at rates comparable to or exceeding extraterrestrial delivery.

The research also has implications beyond Earth. If simple planetary atmospheres exposed to ultraviolet light can generate biologically relevant molecules, then similar processes may occur on other worlds, expanding the range of environments considered potentially habitable. In exoplanet studies then, detecting sulfur-bearing compounds in an atmosphere does not necessarily indicate life; rather, such signatures might also reflect atmospheric chemistry capable of producing life’s precursors.

This interdisciplinary study was supported by NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, among other organisations. McGlynn was a CIRES sabbatical fellow working with Professors Ellie Brown and Maggie Tolbert during the research. The study represents a major advance in linking atmospheric photochemistry with the early evolution of life’s molecular building blocks on Earth and possibly beyond.

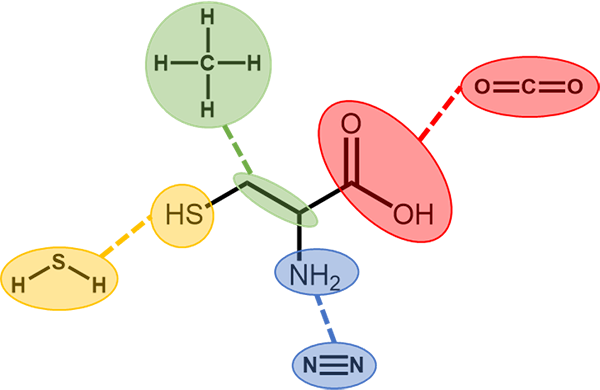

Cysteine is a unique amino acid with a sulfur at one end. This sulfur enables key functions in biology including the movement of electrons and the formation of bonds. Credit: Nate Reed

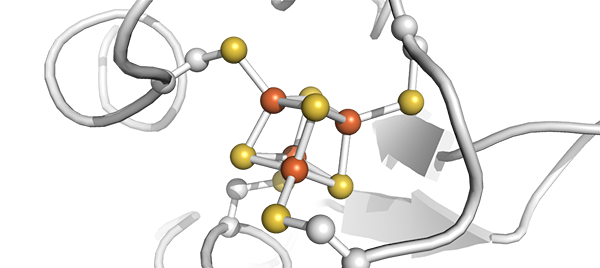

Ferredoxin is a type of protein found across biology with a key role in the movement of electrons. In this figure iron is shown in red and sulfur in yellow (protein database code 1clf). It is the co-occurrence of both Fe and S that allow the special electron transfer properties of ferredoxin which enable many reactions in metabolism and may have been crucial to life’s emergence. Credit: Shawn McGlynn

-

- Department of Chemistry, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder,CO 80309

- Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309

- Department of Chemistry, College of Arts and Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC 27514

- Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599

- Earth-Life Science Institute, Institute of Future Science, Institute of Science Tokyo, Meguro, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan

- Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, Seattle, WA 98104

- Biofunctional Catalyst Research Team, RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, Wako 351-0198, Japan

- Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309

*Corresponding authors email: mcglynn@elsi.jp or eleanor.browne@colorado.edu.

Contacts:

Thilina Heenatigala

Director of Communications

Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI),

Institute of Science Tokyo

E-mail: thilinah@elsi.jp

Tel: +81-3-5734-3163 / Fax: +81-3-5734-3416Shawn Erin McGlynn

Associate Professor

Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI),

Institute of Science Tokyo

E-mail: mcglynn@elsi.jp